Characteristics of Cultural Intelligence

Main Definitions

As we all know, emotional intelligence (EQ) is one’s ability to manage emotions in interpersonal situations. Similarly, cultural intelligence (CQ) is a measure of one’s ability to work with and adapt to members of other cultures. Like EQ (but unlike IQ), CQ can be developed and improved over time with training, experience, and conscious effort.

Culture includes the shared values, norms, rules, and behaviors of an identifiable group of people who share a common history and communication system. There are many types of culture, such as national, organizational, and team. In this article, we discuss principles of intercultural communication in the context of national cultures, which tend to be more permanent and enduring than other types of culture. When people with high CQ encounter unfamiliar encounters, they possess a variety of the skills displayed in Table 4.2 and discussed throughout the text.

Respect, Recognize, and Appreciate Cultural Differences

Cultural intelligence is built on attitudes of respect and recognition of other cultures. This means that you view other cultures as holding legitimate and valid views of and approaches to managing business and workplace relationships. A great deal of research has examined the role of cultural diversity in the workplace. These studies have shown that a mix of cultural groups in terms of national culture, ethnicity, age, and gender leads to better decision making.

Be Curious About Other Cultures

As a college student, you are in a stage of life that gives you unique opportunities to acquire cross-cultural experiences. Consider the following options: studying abroad, learning a language, developing friendships with international students on campus, and taking an interest in and learning about a particular culture.

Take an interest in a culture and routinely learn about it:

- Watch films, television, documentaries, news, and other video of the culture. It’s increasingly easy to access video of other cultures. This allows you to observe many aspects of the culture in context with visual and auditory cues.

- Follow the business culture of a country. Many websites contain global business news sections with both text and videos. For example, consider the following: Bloomberg Businessweek, CNBC, Time, Foreign Exchange, and CIBERweb.

- Take courses and attend events related to particular cultures. Your university offers numerous opportunities, including taking courses about international and intercultural topics and attending symposia that feature international speakers.

- Make friends with people who live in other cultures and communicate online. You might try to make friends abroad and communicate frequently via email, chat, and online calls.

Avoid Inappropriate Stereotypes

Stereotyping about cultures can also be dysfunctional, counterproductive, and even hurtful. People tend to form two types of stereotypes when interacting with members of other cultures: projected cognitive similarity and outgroup homogeneity effect:

- Projected cognitive similarity is the tendency to assume others have the same norms and values as your own cultural group. This occurs when people project their own cultural norms and values to explain the behaviors they see in others.

- Outgroup homogeneity effect is the tendency to think members of other groups are all the same. Psychologically, this approach minimizes the mental effort needed to get to know people of other groups. Practically speaking, it is counterproductive to developing effective working relationships with members of other cultures.

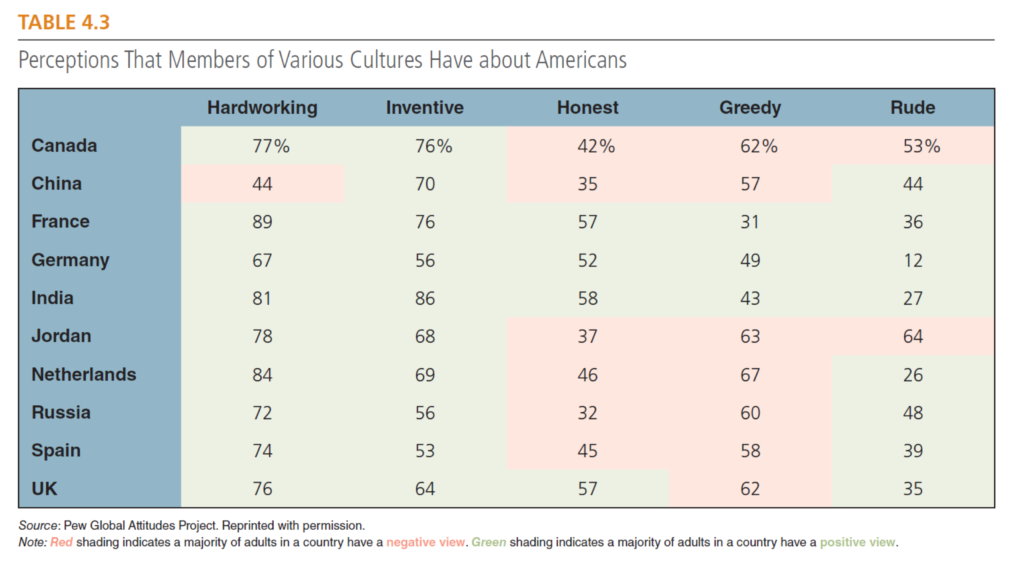

For instance, members of other cultures often form stereotypes of Americans based on news stories as well as popular culture (i.e., films, television shows, music). Typically, most people around the world hold mixed views of Americans (see Table 4.3). Even in countries where the majority of adults view Americans as dishonest or greedy, they also view Americans as hardworking and inventive.

Major Cultural Dimensions

In this section, we describe recent research on cultural norms and values among businesspeople throughout the world. This research, conducted by the GLOBE group (which includes dozens of business researchers around the world), is based on surveys and interviews of about 20,000 business leaders and managers in 62 countries Cultural dimensions are fairly permanent and enduring sets of related norms and values.

The GLOBE group found that cultures can be grouped into eight dimensions. They are classified as (1) individualism and collectivism, (2) egalitarianism and hierarchy, (3) assertiveness, (4) performance orientation, (5) future orientation, (6) humane orientation, (7) uncertainty avoidance, and (8) gender egalitarianism. By understanding these eight dimensions, you can get a good sense of the underlying motivations and goals that impact acceptable behaviors within a culture.

Individualism refers to a mind-set that prioritizes independence more highly than interdependence, emphasizing individual goals over group goals, and valuing choice more than obligation. Below figure displays country rankings for individualism and collectivism in society. Of the countries we are considering here, China has the highest ranking for collectivism and the Netherlands has the lowest.

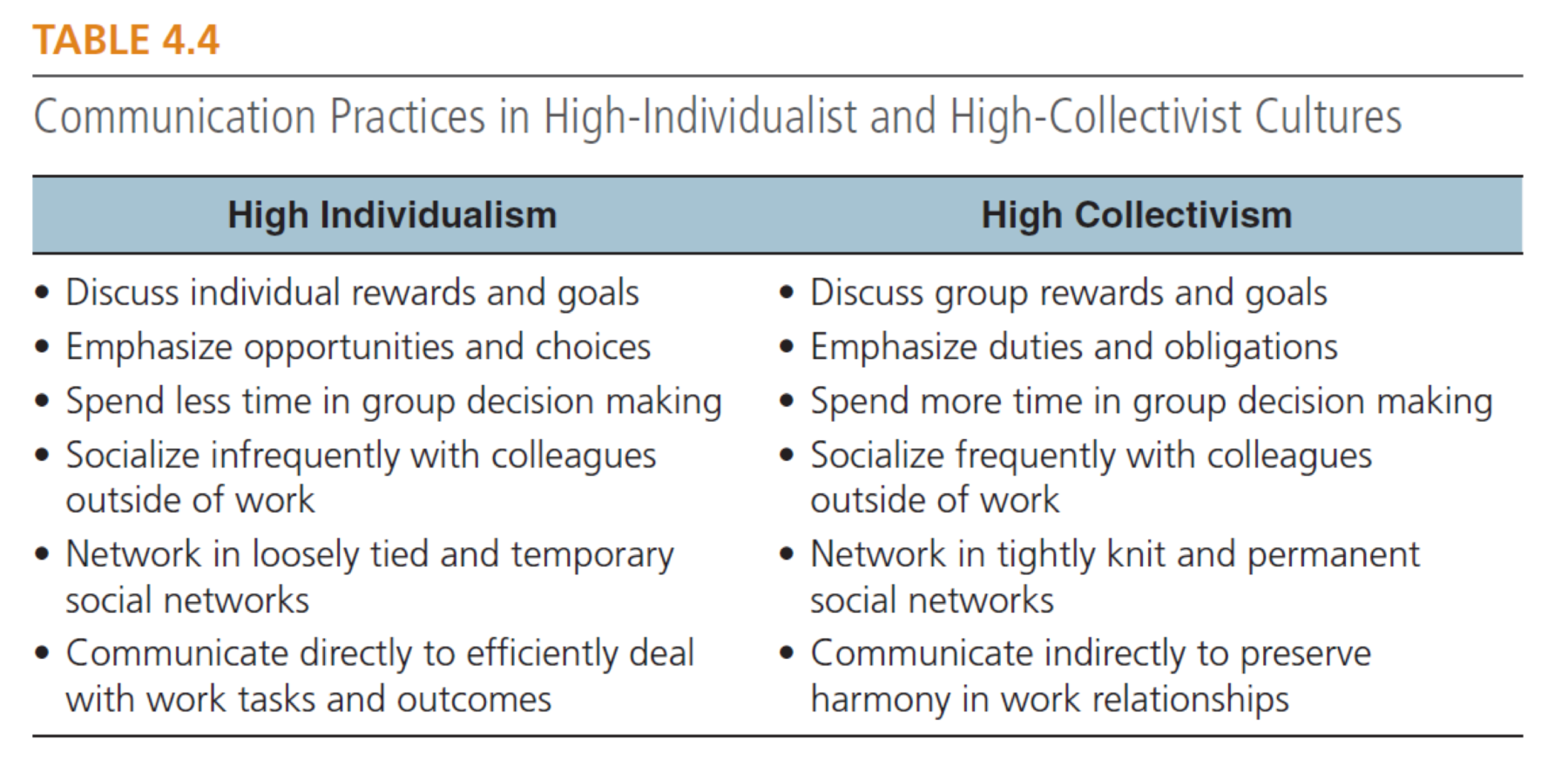

Collectivism refers to a mind-set that prioritizes interdependence more highly than independence, emphasizing group goals over individual goals, and valuing obligation more than choice. Figure 4.3 displays country rankings for individualism and collectivism within companies. In many cases these rankings differ from norms and values in society at large. Table 4.4 shows communication practices normally associated with high individualism and high collectivism.

Communication Practices in High Individualist and High Collectivist Cultures

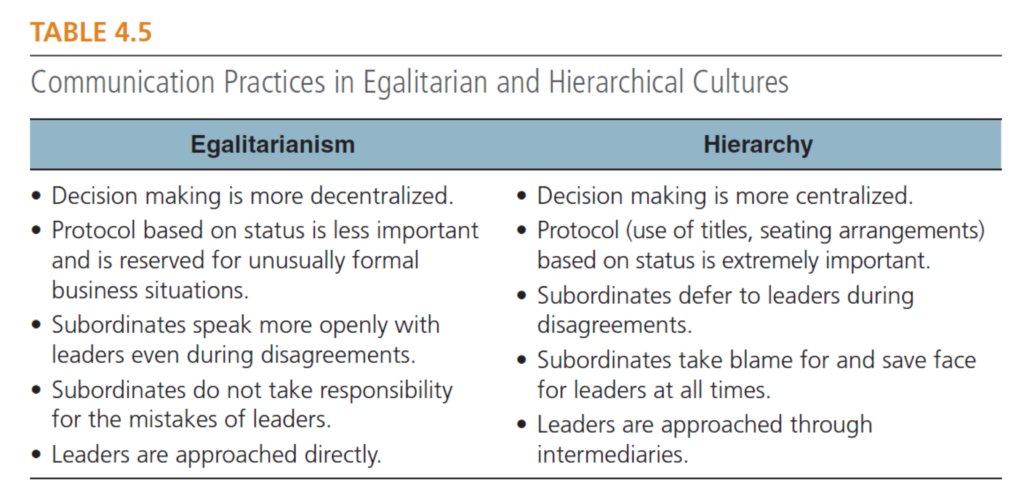

All cultures develop norms for how power is distributed. In egalitarian cultures, people tend to distribute and share power evenly, minimize status differences, and minimize special privileges and opportunities for people just because they have higher authority. In hierarchical cultures, people expect power differences, follow leaders without questioning them, and feel comfortable with leaders receiving special privileges and opportunities. Power tends to be concentrated at the top. Table 4.5 presents communication practices normally associated with hierarchy and egalitarianism.

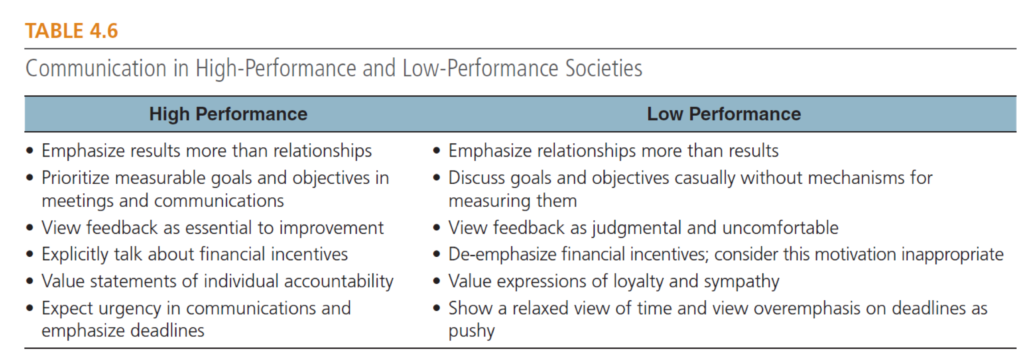

Performance orientation (PO) is “the extent to which a community encourages and rewards innovation, high standards, and performance improvement.” Of all cultural dimensions, societies cherish this one the most, especially in business. Table 4.6 presents communication practices normally associated with high- and low-performance orientation.

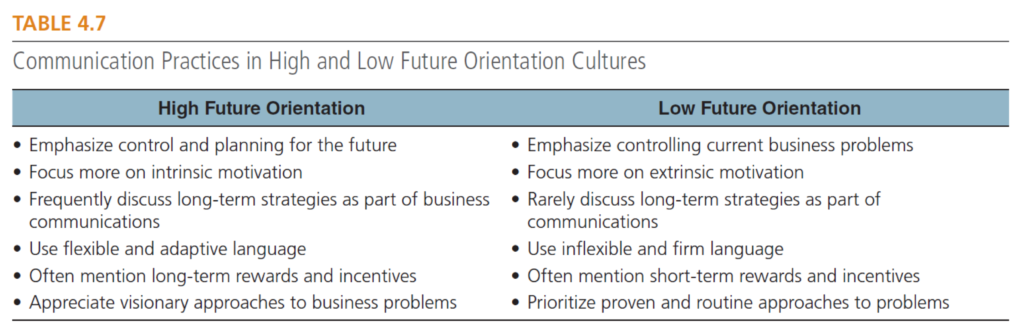

Future orientation (FO) involves the degree to which cultures are willing to sacrifice current wants to achieve future needs. Cultures with low FO (or present-oriented cultures) tend to enjoy being in the moment and spontaneity. They are less anxious about the future and often avoid the planning and sacrifices necessary to reach future goals. By contrast, cultures with high FO are imaginative about the future and have the discipline to carefully plan for and sacrifice current needs and wants to reach future goals. Table 4.7 presents communication practices normally associated with high and low future orientation.

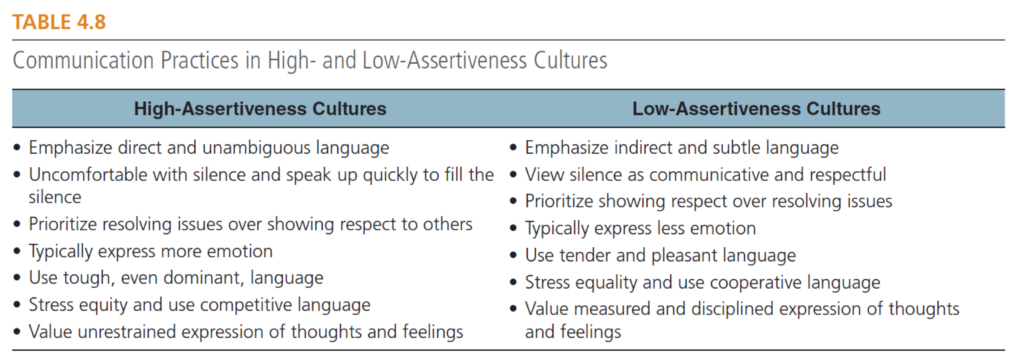

The cultural dimension of assertiveness deals with the level of confrontation and directness that is considered appropriate and productive. Typically, North Americans and Western Europeans are the most assertive in business situations, whereas Asians tend to be less assertive. Table 4.8 presents communication practices normally associated with high and low assertiveness.

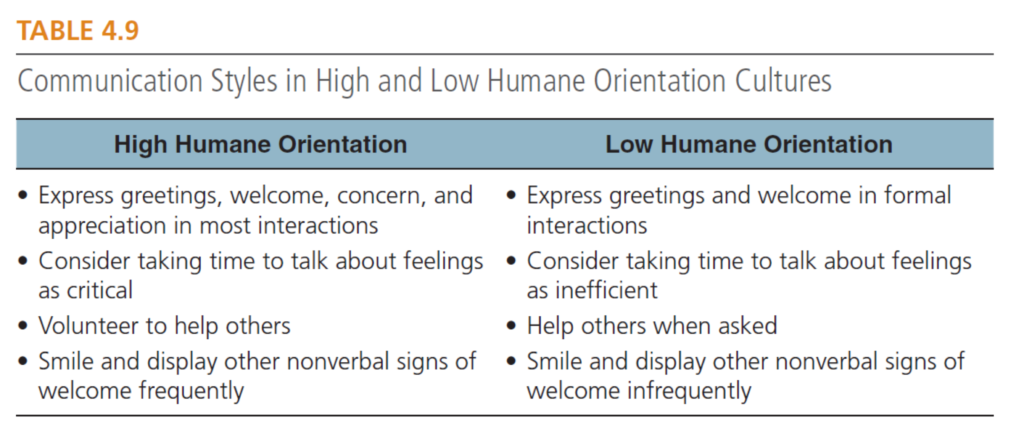

Humane orientation (HO) is “the degree to which an organization or society encourages and rewards individuals for being fair, altruistic, friendly, generous, caring, and kind.” In high HO cultures, people demonstrate that others belong and are welcome. In low HO cultures, the values of pleasure, comfort, and self-enjoyment take precedence over displays of generosity and kindness. Table 4.9 presents communication practices normally associated with high and low humane orientation.

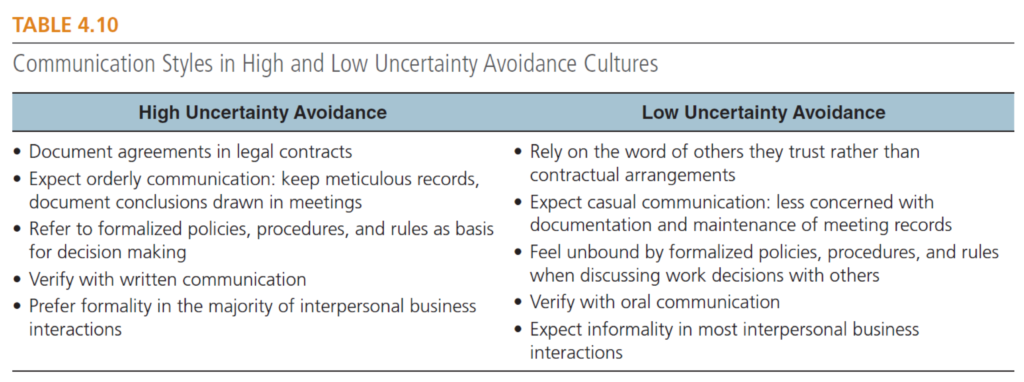

Uncertainty avoidance (UA) refers to how cultures socialize members to feel in uncertain, novel, surprising, or extraordinary situations. In high UA cultures, people feel uncomfortable with uncertainty and seek orderliness, consistency, structure, and formalized procedures. In low UA cultures, people feel comfortable with uncertainty. Figure 4.10 displays country rankings for uncertainty avoidance. Table 4.10 presents communication practices normally associated with high and low uncertainty avoidance.

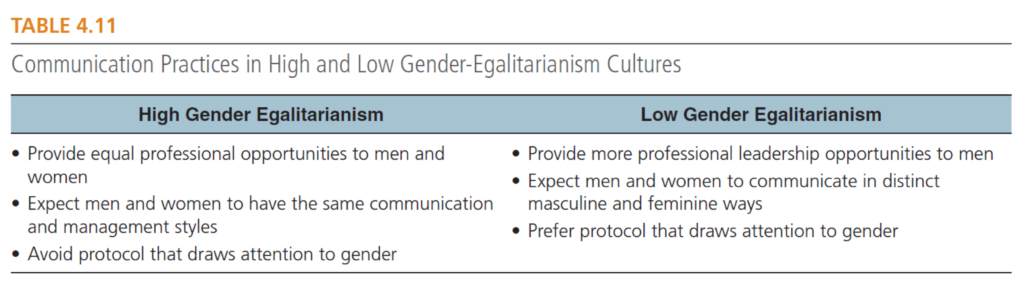

Gender egalitarianism deals with the division of roles between men and women in society. In high gender-egalitarianism cultures, men and women are encouraged to occupy the same professional roles and leadership positions. In low gender-egalitarianism cultures, men and women are expected to occupy different roles in society. In Table 4.11 you will find communication practices normally associated with high and low gender-egalitarianism cultures.

Building and Maintaining Cross-Cultural Work Relationships

- Establish Trust and Show Empathy

- Adopt a Learner Mind-set

- Build a Co-Culture of Cooperation and Innovation

Business managers often start relationships from a position of needing to earn the trust of others. This is further complicated when working across cultures, where the beliefs that most people are fair or most people can be trusted may be less prominent than in North America. China, Canada, the United States, the Netherlands, and Saudi Arabia are considered to be high-trust cultures, meaning that their citizens are more conditioned to trust. In contrast, Mexico, Brazil, and France are considered to be low-trust cultures.

In Table 4.13, you will find examples from Brazil, Russia, India, and China (often called the BRIC countries because of their expected strategic importance for business during the 21st century). This table includes the types of customs and etiquette you should become aware of before traveling to another country for business, including appropriate versus taboo topics of conversation, conversation style, punctuality and meetings, dining, touching and proximity, business dress, and gift giving.

Source: Based on Cardon, P.W. (2016). Crisis Communication and Public Relations Messages (Bonus Chapter). In Business Communication. McGraw Hill Education.