Disruptive Technologies

Introduction

Kodak once had 145,000 employees, a market share near 90 percent, and profit margins so good an executive once bragged that any products more lucrative than film were likely illegal. No firm was closer to photographers. No brand was more synonymous with photographs. Emotionally moving images were known as “Kodak moments.” And yet a firm with so much going for it was crushed by the shift that occurred when photography went from being based on chemistry to being based on bits. Today Kodak is bankrupt, it’s selling off assets to stay alive, and its workforce is about one-fourteenth what it used to be.

The fall of Kodak isn’t unique. Many once-large firms fail to make the transition as new technologies emerge to redefine markets. And while these patterns are seen in everything from earthmoving equipment to mini-mills, the tech industry is perhaps the most fertile ground for disruptive innovation. The market-creating price elasticity of fast/cheap technologies acts as a catalyst for the fall of giants.

The Characteristics of Disruptive Technologies

The term disruptive technologies is a tricky one, because so many technologies create market shocks and catalyze growth. Lots of press reports refer to firms and technologies as disruptive. But there is a very precise theory of disruptive technologies (also referred to as disruptive innovation—we’ll use both terms here) offered by Harvard professor Clayton Christensen that illustrates giant-killing market shocks, allows us to see why so many once-dominant firms have failed, and can shed light on practices that may help firms recognize and respond to threats.

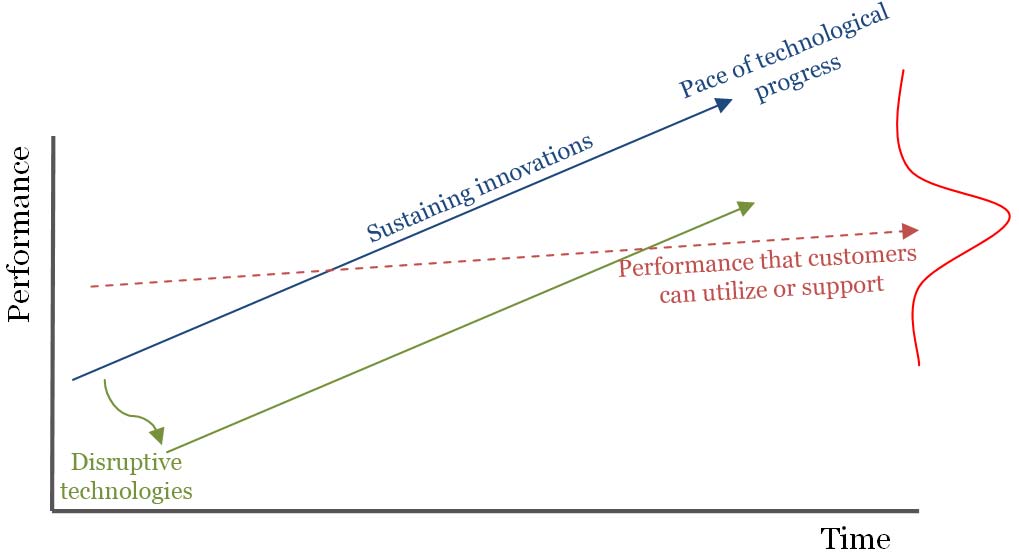

In Christensen’s view, true disruptive technologies have two characteristics that make them so threatening. First, they come to the market with a set of performance attributes that existing customers don’t value. Second, over time the performance attributes improve to the point where they invade established markets (See Figure 5.3 below).

These attributes are found in many innovations that have brought about the shift from analog to digital. The first digital cameras were terrible: photo quality was laughably bad (the first were only black and white), they could only store a few images and did so very slowly, they were bulky, and they had poor battery life. It’s not like most customers were lined up saying “Hey, give me more of that!” Much the same could be said about the poor performance of early digital music, digital video, mobile phones, tablet computing, and Internet telephony (Voice over IP, or VoIP), just to name a few examples. But today all of these digital products are having a market-disrupting impact. Digital cameras have all but wiped out film use, the record store is dead, mobile phones for many are their only phone, tablets are selling faster than laptops, Internet phone service is often indistinguishable from conventional calls, and Skype can be considered the world’s largest long-distance phone company. All of these changes were enabled by fast/cheap technologies…

Figure 5.3 The Giant Killer

Incumbent technologies satisfy a sweet spot of consumer needs. Incumbent technologies often improve over time, occasionally even overshooting the performance needs of the market. Disruptive technologies come to market with performance attributes not demanded by existing customers, but they improve over time until the innovation can invade established markets. Disruptive innovations don’t need to perform better than incumbents; they simply need to perform well enough to appeal to their customers (and often do so at a lower price).

Source: Adapted from Shareholder Presentation by Jeff Bezos, Amazon.com, 2006.

Bitcoin: A Disruptive Innovation for Money and More?

Bitcoin is the transaction method favored by cybercriminals and illegal trade networks like the now-shuttered Silk Road illegal drugs bazaar. It’s not backed by gold or government and appeared seemingly out of thin air as the result of mathematics performed by so-called “miners.” It’s been a wildly volatile currency, where an amount that could purchase a couple of pizzas today would be worth over $6 million a little over three years later. Its one-time largest exchange handled millions in digital value, yet it was originally conceived as the “Magic: The Gathering Online card eXchange” (Mt. Gox), and that service suffered a massive breach where the digital equivalent of roughly $450 million disappeared. Despite all this, many think bitcoin might upend money as we know it enough that venture capitalists have been pouring their coin into bitcoin start-ups, topping $1 billion by late 2015.

The B symbol with two bars is used to refer to bitcoin.

Many don’t even know what to call bitcoin. Is it a cryptocurrency, a digital currency, digital money, or virtual currency? The US government has ruled that bitcoin is property (US Marshals have auctioned off bitcoins seized from crooks). While Goldman Sachs and UBS were initially dismissive of bitcoin’s future, Deloitte has written that the negative hype has underestimated the technology’s potential to revolutionize not just payments but all sorts of asset transactions. The Bank of England has issued a report describing bitcoin as a “significant innovation” that could have “far-reaching implications.”

How It Works

Bitcoins are transferred from person to person like cash. Instead of using a bank as a middleman, transactions are recorded in a public ledger (known as a blockchain in bitcoin speak) and verified by a pool of users called miners. The miners get an incentive for being involved: they can donate their computer power in exchange for the opportunity to earn additional bitcoins, and sometimes, some modest transaction fees (this means bitcoin is peer-produced finance. While the ledger records transactions, no one can use your bitcoins without a special password (called a private key and usually stored in what is referred to as a user’s bitcoin wallet, which is really just an encrypted holding place). The technology behind this is open-source and considered rock solid. Passwords are virtually impossible to guess, and verification makes sure no one spends the same bitcoins in two places at once.

Benefits

Much of bitcoin’s appeal comes from the fact that bitcoins are transferred from person to person like cash, rather than using an intermediary like banks or credit card companies. Getting rid of card companies cuts out transaction fees, which can top 3 percent. Overstock.com was one of the first large online retailers to accept bitcoin. Its profit margins? Just 2 percent. Needless to say, Overstock’s CEO is a bitcoin enthusiast. Bitcoin also opens up the possibility of micropayments (or small digital payments) that are now impractical because of fees (think of everything from gum to bus fare to small donations).

Bitcoin could also be a boon for international commerce, especially for cross-border remittance and in expanding e-commerce in emerging markets. Family members working abroad often send funds home via services like Western Union or MoneyGram, but these can cost $10 to $17 for a $200 transfer and take up to five days to clear in some countries. A bitcoin transfer would be immediate and could theoretically eliminate all transaction fees, although several firms are charging small fees to ease transactions and quickly get money moved from national currency to bitcoin and back. They’re going after a big market, as global remittances total over half a trillion dollars. Bitcoin might also lubricate the wheels of commerce between nations where credit card companies and firms like PayPal don’t operate, and where internationally accepted cards are tough to obtain. Less than one-third of the population in emerging markets have any sort of credit card, but bitcoin could provide a vehicle to open this market up to online purchases.

Civil libertarians like the idea of transactions happening without the prying eyes of data miners inside card companies, having their transaction history shared by others, or the government. As Wired points out, bitcoin straddles the line between transparency and privacy. All transactions are recorded in the open, via the blockchain, but individuals can be anonymous. You can create your anonymous private key and have someone transfer funds to you or earn bitcoin via mining and no one can see who you are. While governments can try to shut down or legislate bitcoin activity within their borders, there’s no bitcoin organization that controls money flows. It’s been noted that following the revelations in WikiLeaks, Visa, Mastercard, and PayPal refused donations to WikiLeaks. In that aftermath, Bitcoin became the go-to vehicle for those supporting WikiLeaks’ efforts. There’s was no central organization to “freeze” a bitcoin account or a central technical resource to impound or shut down. If a bitcoin transaction is not permitted in your country, go abroad and you’ve got full access to everything in your wallet.

Source: Information Systems: A Manager’s Guide to Harnessing Technology, v. 2.0 by John Gallaugher

Assessment Tasks:

- Explain what is meant by Innovator’s Dilemma

- Why do big firms fail? Can the Innovator’s Dilemma explain big firm failures? Illustrate your answer.

- Explain why in your opinion did Kodak fail, what did they do right and what did they do wrong?

- Select a company and present an argument that it will fail in the next 10 years if it continues to do things in the same way.

NOTICE! AEssay Team Experts have already completed this assignment and is ready to help You with it. Please contact our support team via online chat to request your discount coupon code and order this essay cheaper.